Keith’s World

Author Brad Gooch discusses his new biography of the late artist and activist Keith Haring

By Tim Murphy

After working as a model in 1970s and ’80s New York City, Brad Gooch became an author. He wrote poetry, novels and memoirs, including “Smash Cut,” about his decade-long relationship with film producer Howard Brookner, who died of AIDS in 1989. He also wrote acclaimed biographies of literary legends Frank O’Hara and Flannery O’Connor.

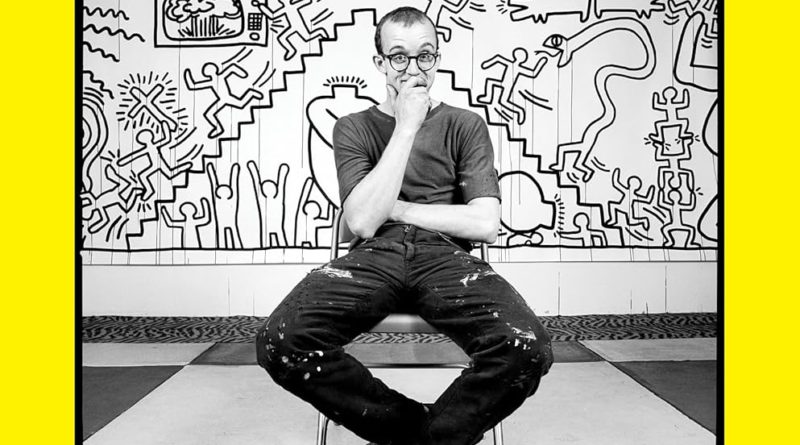

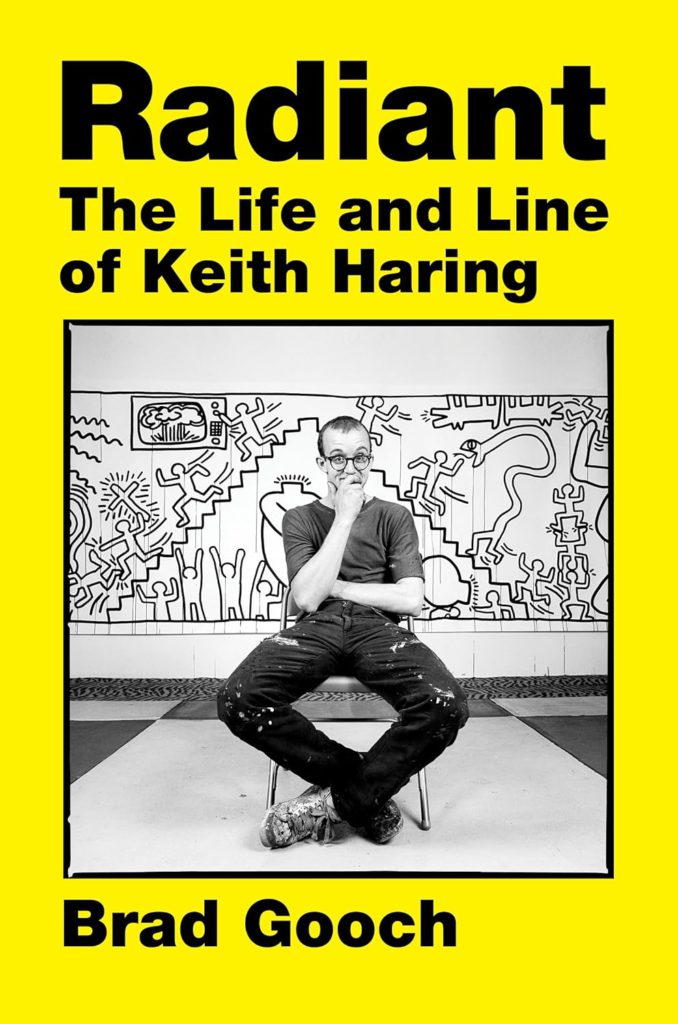

His latest biography is “Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring.” It’s a fat, juicy and extremely well-researched account of the brief but explosive life and career of the beloved pop artist, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1990 at age 31.

Below is a short version of a long interview that Gooch, 72, gave to The Caftan Chronicles, the Substack newsletter by longtime POZ contributing writer Tim Murphy.

What is a typical day like?

I have two kids — Walter, 9, and Glenn, 5. Today, I woke up at 6:40 a.m. listening to Walter play chess on this kids’ app. My partner, Paul Raushenbush, is 59 and is a minister who is president and CEO of the Interfaith Alliance. We live in Chelsea [in Manhattan].

I make breakfast for the boys. Paul goes to the gym, and I take the boys to school a few blocks away and then go to my separate office nearby. Then I’ll see my trainer. Then I’ll go home, and we have dinner together. The boys and I will watch a short video, and then I put them to bed. I watch PBS Newshour and read, and then I sleep.

What is it like having kids rather late in life?

It’s been great. I think 60 is a good age to start having children. I think I would’ve been a horrible parent in my 30s because I’d have wanted to go out all the time, network, travel or work on my career.

You grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania — just like Keith!

There were a lot of things about [writing about] Keith that came naturally to me. We were living in New York City at the same time. Both of us were born in the 1950s.

His parents didn’t want him to be an artist, and my parents didn’t want me to be a poet. Both our parents were Republicans. Keith’s mother said to me, “Keith never said the words gay or AIDS to us,” and I completely understood that. I don’t think I ever said the word gay to my parents, but when my lover, Howard Brookner, had AIDS, he’d come home with me in his wheelchair, and my parents accepted all of this, but we never said, “We are lovers, and one of us has AIDS.”

After all this immersion into Keith’s life and psyche, who do you think he was?

Keith had this innocent, almost naïve quality combined with this enormous energy. He was really on a mission. He was an unusual artist because he was so generous in terms of [promoting] other people’s works.

He did a huge amount of public and community art that he didn’t seek compensation for.

And he set up the Keith Haring Foundation at age 28 and said that half the funds would go to charities involving AIDS and children, and that’s the case to this day. But there were other aspects to him that I think were mostly explained by immaturity.

For one thing, as your book makes clear, he was a real fame whore.

His whole celebrity thing was kind of extreme. I mean, if you have Andy Warhol criticizing you for wanting to have your picture taken so badly. [Laughs.] He had this gaga fanboy quality.

Your book vividly captures the frantic pace of Keith’s work and his entire life, especially as he became aware that he likely didn’t have long to live.

I had a far greater respect for him by the time I was finishing the book. I think the way he faced death was amazing. Instead of melting away, he revved everything up and created some of the best work that he ever made. In the ’90s, it seemed like he was going to fade away, but in so many ways, we’re living in Keith’s world now.

He’s had a huge surge of popularity in the 21st century. You see his work everywhere.

The world caught up to him. So many of the things he was propelled by in his work are now understandable. The idea of democratization, that art is for everybody. Not having this huge distinction between high and low art and the availability of every surface, activist messaging and the licensing of products that he was so criticized for at the time. All of this is our current world.

Your book really captures the mood arc of the ’80s — from a decade that starts as the carryover of the hedonism of the ’70s and then darkens and saddens because of AIDS.

It’s true that it started with the infectious, liberating tone of the late ’70s. Then you get this scary article in The New York Times in 1981 [about the first AIDS cases].

I remember someone telling me that year that he had it — whatever we called it — the gay virus, and I almost passed out.

You’re HIV negative?

I didn’t know that until 1987, when I took an actual test. [Even once the test came out in 1985], people weren’t taking it because there was nothing you could do about positive results. Keith was healthy for a long time in the ’80s, but he assumed he had the virus because of the life he’d led at the baths. But the epidemic didn’t really start manifesting until the mid-’80s. Suddenly, it seemed like every other person was either HIV positive or sick, and you were going to memorial services every night. That’s a tremendously dark period that Keith dies at the end of.

What was modeling like?

There were great aspects to it. I was suddenly invited into all these cool places and rich people’s houses and dinners where I sat next to [famed ballet dancer Rudolf] Nureyev, and he put his hand on my thigh. But I watched a lot of boy and girl models get destroyed by all that.

Also, gay photographers only wanted to work with straight models, so if they sensed that you were gay, they didn’t want to use you.

Ew, that’s gross. So how do you see your present self in the context of your past self?

The main things that define my present life are having this family and writing. I’m living my best life now, but I also have a kind of PTSD from having lived through AIDS and the loss of Howard. In the ’90s, a numbness set in for me emotionally and sexually. I just went to Madonna’s Celebration concert at Madison Square Garden, and there’s a five-story-high image of both Keith Haring and Howard [when she sings “Live To Tell” as a memorial of her friends and others lost to AIDS].

Howard is wearing this striped shirt from Brooks Brothers. That’s what I was focusing on. [Pauses.] One reason I’m glad to have this book about Keith out there is that it tells the story of AIDS at that moment, because I don’t think young queer people know it. That period is still always with me. Through the 2000s, I’d wake up in the middle of the night with this fear of death. That didn’t go away until I became a father.

Why do you think that is?

I guess now I have the feeling or the illusion that there’s a future. In a Rolling Stone interview Keith did when he came out as a person with AIDS, he said, “Well, I don’t have dreams of the future anymore.” That really stuck with me. But somehow, now, with kids, I have this sense that they’re going on into the future.

Tim Murphy is a contributing writer at POZ. This column is a project of TheBody, Plus, Positively Aware, POZ and Q Syndicate, the LGBTQ+ wire service. Visit their websites — http://thebody.com, http://hivplusmag.com, http://positivelyaware.com and http://poz.com — for the latest updates on HIV/AIDS.